Academy Contributors Academy Contributors

Knowing Your Crew

By Gary Priest, Curator of Animal Care Training, San Diego Zoo Global Academy

The year 2017 is already half spent, and this is my final submission in the "nautical" series of columns. The nautical analogy was designed to help you understand how to launch your own institution's Academy staff development and training program. Since January, topics included: The Importance of Encouragement in Managing Change; Developing a Vision for the Destination; Charting a Course; Recognizing and Using the Prevailing Wind and Currents; and Knowing How to Tack When Conditions Require It. As your ship's master, you must know your crew—and this final installment is dedicated to that understanding.

In 2009, the Johnson Graduate School at Cornell University published an interesting study undertaken by social scientists J. Stuart Bunderson and Jeffery A. Thompson. Their paper is titled "The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings and the Double-edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work."1

In their work, Bunderson and Thompson interviewed keepers from 157 different institutions in the United States and Canada. As the data were gathered and studied, the researchers identified several somewhat surprising themes about animal keepers and how they see themselves.

- Keepers Are Well Educated—In 2004, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 82 percent (4 out of 5) of professional animal care staff hold a 4-year college degree. In the 13 years since 2004, based on the increasingly competitive environment, I suspect that today this figure is closer to 9 out of 10 animal care staff that hold at least a 4-year degree.

- Sacrifice—Most keepers willingly sacrifice in a variety of ways before they finally break into this highly competitive profession. Though not a particularly high-paying profession, the data revealed that many keepers expressed feeling "excited, lucky, or fortunate" to be in the profession. Considering the hard work and sacrifice, this finding is really astonishing and important.

- A "Calling"—Perhaps equally important, the most frequently coded category researchers collected was this: over 90 percent of those interviewed described their work as a sort of calling. Caring for animals, breeding endangered species, and working to save animals from extinction is central to what truly matters to them in their work.

- Motivation and Money—The second most frequent comment, which focused on money, also presents a surprise. Animal care workers are not strongly motivated by acquiring more money, but rather by passions fueled by a deep commitment to the care of the animals they are responsible for. Having sacrificed to launch their career, this sacrifice and commitment is refreshed financially with each paycheck. Perhaps it is only natural that keepers might resent anything—including the opportunity for continuing education—that seems to take them away from practicing their profession. So, what to do?

Your animal care employees are intelligent, well educated, and passionate about their work. Most have sacrificed a great deal to engage this deep passion. I suggest that these common attributes, shared by so many keepers, can be leveraged to help them understand that your organization is supporting them in their quest to learn best practices, which are found in every animal care training course featured in your institution's Academy catalog.

Professional keepers should never stop learning about animal care. As a tool your institution is providing to help keepers develop stronger professional skills, the Academy should complement, not compete with, your staff's passion. As your institution's administrator, success comes from presenting the Academy in a way that helps staff understand and appreciate that the Academy's content goes hand in hand with their interest in lifelong learning about animals, and the best practices for animal care.

1The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings and the Double-edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work. Bunderson, S.J., Thompson, J.A., 2009. Johnson Graduate School. Cornell University.

For any questions, contact Gary Priest, curator of animal care training, San Diego Zoo Global Academy, at gpriest@sandiegozoo.org.

Getting Better All the Time:

An Enlightened Caregiver's Creed on Serving Animal Interests and Well-being

By James F. Gesualdi By James F. Gesualdi

To keep ahead, each one of us, no matter what our task, must search for new and better methods, for even that which we now do well must be done better tomorrow.

—James F. Bell

Note: This Creed, like all of our efforts to develop ourselves and serve animals and others, is a work in progress. It truly reflects the heart of the art of caregiving.

- We appreciate and understand that people are concerned about the well-being of animals (whether in our care, in the wild, within other settings, and/or in our homes).

- We share that concern and constructively act upon it every day.

- We are humbled and grateful for the opportunity to dedicate ourselves to the well-being of the animals in our loving care.

- While respectful of differences, the one difference we focus on daily is the positive difference we can make in the lives of animals—here and everywhere.

- We thoughtfully consider any reasonable concern, and constantly review ongoing developments here and throughout the world, so as to continuously improve our service on behalf of animals.

- We put proactive thinking into good practices as we change and innovate in ways that incorporate the best interests of the animals.

We do the best we can with what we have and when we know better, we do better.

—Maya Angelou

Please email me at jfg@excellencebeyondcompliance.com to share the good you are doing (as only you can), or with any comments or questions on this column or suggestions for future ones. For upcoming workshops and sessions, contact: info@excellencebeyondcompliance.com.

© 2017 James F. Gesualdi, P.C. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. This is not, nor should it be construed as, legal advice.

Something Fishy Is Going On Something Fishy Is Going On

By Dr. Rob Jones, "The Aquarium Vet"

Batoids is the correct term for skates and rays, which have a dorsoventrally flattened body, and their pectoral fins have become enlarged and round (wings). Many batoids have venomous spines (barbs) on the dorsal part of their tail. Some are near the tip of the tail, while others are more near the base of the tail. Barbs are used only in defense and are not used aggressively. Stingray barbs are one of the major risks of dealing with elasmobranchs. We are all too painfully and sadly aware of the Steve Irwin incident, as well as the aquarist at the Singapore aquarium in 2016.

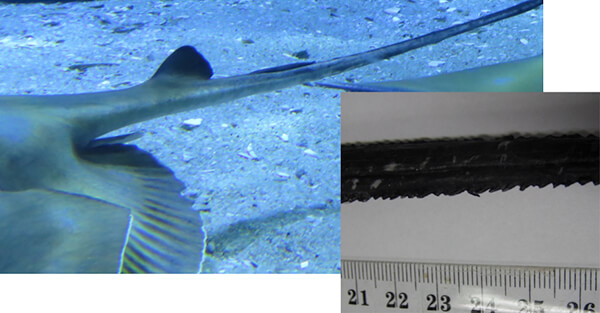

A stingray barb is covered with two rows of sharp, flat spines (see Figures A and B). Underneath these spines are two longitudinal grooves, which run along the length of the spine and enclose venom-secreting cells. A layer of epidermis covers the barb and venom-secreting tissues, and it peels back when the barb enters skin. The barb may break off as it exits the wound and stay within the victim, causing prolonged envenomation.

Figure A: Barb (white arrow) located at the base of the tail of a southern eagle ray (Myliobatis australis); note the dorsal fin (yellow arrow). Figure B: Close up of section of a barb from a smooth ray (Dasyatis brevicaudata); note the serrated edge. Scale is in centimeters.

The barbs contain a nasty cocktail of bacteria, and infections can occur after an injury. The venom contains:

- Large molecular-weight polypeptides

- Serotonin, a smooth muscle relaxant

- Hyaluronidase, an enzyme that breaks down hyaluronic acid in tissues and maximizes the spread of the venom through tissues.

Ray barbs and their potential for injury, even death, are not to be taken lightly. One complication with handling rays is that, unlike sharks that are covered in denticles (which make their skin easy to grasp firmly), many ray species are covered in a thick mucous layer. This makes manually restraining rays very difficult, because they are so slippery.

Ray barbs easily penetrate human skin—one colleague's comment was that it was like "a knife going through hot butter." The pain is severe, and because of the shape of the barb, if it has penetrated a significant distance, it can only be removed via surgery.

As with most marine venoms, the one associated with a ray's barb is heat-labile, and the immediate first-aid treatment is hot water. The water needs to be as hot as possible without burning the patient's skin. Relief is very quick with this measure, because the hyaluronidase activity breaks down very quickly above 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius). Medical attention is always needed, because surgery, antibiotics, and pain relief are usually indicated.

To prevent problems, correct handling of rays is essential, and this will be the topic of next month's article.

E-quarist™ Courses—Academy Subscriber Special!

The San Diego Zoo Global Academy is excited to share an additional Academy subscriber benefit regarding our collaboration with Dr. Jones: as an Academy subscriber, you are now entitled to a discount on the e-quarist™ courses.

For more information about the SDZGA discount, or to view our Trial Version, please contact katrina@theaquariumvet.com.au

Visit the Aquarium Vet website at theaquariumvet.com.au.

|