Academy Contributors

Getting Better All the Time:

Changing for Good

By James F. Gesualdi By James F. Gesualdi

To keep ahead, each one of us, no matter what our task, must search for new and better methods—for even that which we now do well must be done better tomorrow.—James F. Bell

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.

—Charles Darwin

Zoological organizations have changed for the better over the years, and they continue to evolve. Some of these innovations emanate from one or more organizations, while others result from zoological community-wide shifts in policies or practices. Every zoological facility changes daily as animals, staff, and guests come and go. Physical changes in exhibits and fiscal changes in funding are among other apparent changes. Fortunately, zoological organizations have demonstrated the capacity to change, which is an important factor in the future sustainability of the zoological world as a force for good.

The nature and limits of change within the zoological community also explain the most pressing challenges facing zoos, aquariums, and marine and wildlife parks today. Heightened public consciousness about animals, stemming from our relationships with those animals in our homes, families, and hearts, contributes to these challenges—and creates corresponding opportunities to do more good. Enhanced understanding about animals, ethical considerations worthy of civil engagement, and other criticisms are now, and perhaps forever, a staple of the operating environment for most every zoological organization.

In short, culture and society, especially here in the US, has changed much faster and more profoundly than the zoological world. A chance encounter with these words from Jack Welch calls attention to the need for awareness: "[i]f the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near." While that might sound harsh, it corresponds to Darwin's take on survival. It also illuminates the path forward, which remains a consistent focus of this column. Simply acknowledging the challenges is a decent start, but more is needed to get unstuck. As James Allen wrote over a hundred years ago, "[p]eople are anxious to improve their circumstances, but are unwilling to improve themselves. They therefore remain bound."

The exciting news is that once we understand the causes behind the effects and challenges before us, we can get to the work of fundamentally changing ourselves, our zoological organizations and community, and even the world, for the better. Perhaps the words of fellow columnists Dr. Rob Jones or Gary Priest, Academy courses, an inspiring book or lecture, or a humbling conversation or constructive criticism can help to discern the reinvention needed to clear the path ahead. Here is a short list of ideas for such reinvention.

- Change our thinking and language about our mission, animals, and each other, including our critics.

- Animal welfare or well-being is the overriding priority every day.

- Commit to continuous improvement to enhancing animal welfare. (The Academy's complimentary Animal Welfare course and Vicino and Miller's Five Opportunities to Thrive discussed therein is a great foundation to build upon.)

- Act in harmony with our highest ideals and our compassion for all life.

- Practice Excellence Beyond Compliance® and the Principles of Constructive Engagement (see Turning Challenges into Opportunities: the Principles of Constructive Engagement, November 2015, available here.

Other ideas have been set out in prior columns or are forthcoming. There is a role for everyone in the zoological community to be a part of this change—caregivers, curators, fund-raisers, construction and maintenance teams, marketers, security, directors and board members, regulators, critics, visitors….

Deep thinking, spirited conversations, and hard work will move us ahead if we choose to seize the opportunities presented.

Changing for the better. Changing for the animals. Changing for good.

Be the change you want to see in the world.

—Mahatma Gandhi

Please email me at jfg@excellencebeyondcompliance.com to share the good you are doing (as only you can), or with any comments or questions on this column or suggestions for future ones. For upcoming workshops and sessions, contact: info@excellencebeyondcompliance.com.

© 2017 James F. Gesualdi, P.C. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. This is not, nor should it be construed as, legal advice.

Something Fishy Is Going On Something Fishy Is Going On

By Dr. Rob Jones, "The Aquarium Vet"

As mentioned in last December's newsletter, the grey nurse (or sand tiger) shark Carcharias taurus is an iconic shark that has been displayed in public aquariums since 1896, when it was first held in the New York aquarium. It practices intrauterine cannibalism, and after a pregnancy of approximately 12 months, two pups are born that are about 1 to 1.2 meters in length and very developed. It is survival of the fittest from day one.

These sharks have traditionally bred poorly in aquariums for a variety of reasons, some of which we now understand and some which still remain unknown. When Dr. Jon Daly and I started researching elasmobranch reproduction in 2004, very little was known. One of the first tasks was to develop a repeatable method of catching sharks; one that was safe for both the aquarists and the sharks. We chose the broadnose sevengill shark Notorynchus cepedianus as our surrogate species. This shark is a viviparous shark like the sand tiger, but does not have the intrauterine cannibalism, and has never been bred in captivity.

A shark catch bag was developed from thick, clear plastic (the material used in soft-top car windows), and divers would go down and catch the shark that had been selected for examination that particular week (see photo below). Each shark was examined every six to eight weeks. Interestingly, the sharks did not seem to avoid the bag and the divers. We also carefully considered the welfare of the sharks during the capture and restraint process, and we developed a scoring system from which a paper was produced (Daly et al. 2007).

For restraint, we used tonic immobility: with the top of the catch bag opened, and holding onto the shark, the animal is turned onto its back. After a brief struggle of 10 to 15 seconds, the shark goes into a catatonic state. Plenty of water with oxygen is then flowed over the mouth area to keep the gills irrigated. We always set a ceiling of 10 minutes for our examinations.

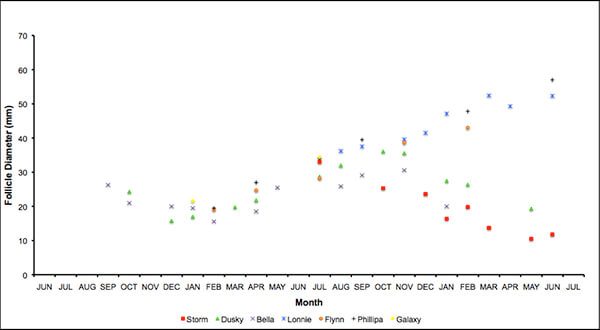

With the females, we started looking at their ovaries using ultrasound, and following their egg development, often over a two-year period. The picture below shows two eggs that were maturing in one of our females ("Lonnie"). The graph details the egg sizes of seven of the female sharks over a two-year period. We would find and measure a minimum of 10 eggs at each examination.

The study ran for five years, and so all of these results were not actually in the same years, but were combined into this one graph. In some of the females, the eggs enlarged to over five centimeters until they ovulated. In other females, the eggs underwent a process of atresia and regressed. What triggered the different responses, we still do not know.

We have since undertaken studies on several species of sharks and rays, but I will always have a soft spot for the sevengills, as they were the first we worked with in the early years. Next month, we will talk about working with the male sharks, and the future of this research.

Reference: Daly J, Gunn I, Kirby N, Jones R and Galloway D (2007). Ultrasound Examination and Behaviour Scoring of Captive Broadnose Sevengill Sharks, Notorynchus cepedianus (Peron, 1807), Zoo Biology 26:113.

E-quarist™ Courses—Academy Subscriber Special!

The San Diego Zoo Global Academy is excited to share an additional Academy subscriber benefit regarding our collaboration with Dr. Jones: as an Academy subscriber, you are now entitled to a discount on the e-quarist™ courses.

For more information about the SDZGA discount, or to view our Trial Version, please contact katrina@theaquariumvet.com

Visit the Aquarium Vet website at theaquariumvet.com |